Why There Will Always Be War

During hard times such as these, we tend to relinquish our individual opinions to those of our respective hiveminds. I am posting this short essay to remind each of us to remember to think for ourselves. I also want to emphasize that this post is in no way meant to provide a rationale for what is going on in Israel and the Gaza Strip right now – think of it as more of a…lament.

During hard times such as these, we tend to relinquish our individual opinions to those of our respective hiveminds. I am posting this short essay to remind each of us to remember to think for ourselves. I also want to emphasize that this post is in no way meant to provide a rationale for what is going on in Israel and the Gaza Strip right now – think of it as more of a…lament.

We can convince ourselves of anything. Let me explain. Humans think by analogy. In more logical thinkers, the analogies become less ambiguous, but in all human thinkers, the emotions and the concepts our minds employ are generalizations; abstractions that ignore particulars. Analogies are false to pure fact; they are comparative matters of judgment. Thus, we are able to apply our thinking inconsistently. For example, we may have one standard related to scientific theories, and another for religious theories; one standard for ourselves, and another for the rest of the world. This system of thought allows us to ignore errors in chains of logic. We can make ourselves unaware of the implications of our thoughts, or ignore the true meaning, context, and consequences of our actions. Our ability to formulate rationalizations to justify and obscure the true causes and conclusions of our cognition from ourselves can be a blessing and a curse.

What is the true nature of human evil? Is it the complete disregard for empathetic compassion – a twisted psyche predisposed for performing malice without semblance of emotional attachment – or is it illustrated by people like David Lewis Rice, who, believing he was a patriot engaged in a secret war against covert communists, murdered an innocent family of four in 1985? Is the true nature of human evil demonstrated by people who are willing to do anything and everything for whatever cause they may champion? All people of such fervent conviction are not dangerous. However, people that deem it necessary to impress their views upon others at all costs are.

What is the true nature of human evil? Is it the complete disregard for empathetic compassion – a twisted psyche predisposed for performing malice without semblance of emotional attachment – or is it illustrated by people like David Lewis Rice, who, believing he was a patriot engaged in a secret war against covert communists, murdered an innocent family of four in 1985? Is the true nature of human evil demonstrated by people who are willing to do anything and everything for whatever cause they may champion? All people of such fervent conviction are not dangerous. However, people that deem it necessary to impress their views upon others at all costs are.

People kill other people for two reasons: survival of self, or survival of ideology. More people have been killed and persecuted in the name of a higher ideal than for any other reason in human history. Racial purity, religious intolerance, and fanatical jingoism come to mind immediately when examining genocidal motivation throughout history. Mass violence has existed since the dawn of man. The Torah chronicles the Jewish massacre of the Amelekites and Midianites. Before that, the Assyrians and Egyptians derooted entire civilizations for enslavement, their version of deterrence. The Greeks of Athens annihilated the nations for their own self-interests. The Punic Wars ended with Rome wiping Carthage and its citizens from history. Genghis Khan left half the world burning in his turbulent wake. The Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, the colonization of the Americas, the Salem Witch Trials, the inevitable collapse and displacement of the American Indian tribes, the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, the Stolen Generation of Australia, the Hutus and Tutsis, Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge, Bosnia, Rwanda, Sudan – the list could go on and on – are some of our most grievous examples. Outlying reasons may have varied, but the rationale at the heart of each matter has remained remarkably single-minded, even as the human mind supposedly evolves and betters itself. Cynicism would dictate that only the methods with which we use for killing, and the methods with which we use to justify killing have evolved over the ages. Every shred of information we receive is tainted by a generational loss, each source polluted by an inherent human bias or deliberate rhetoric designed to sway us this way or that.

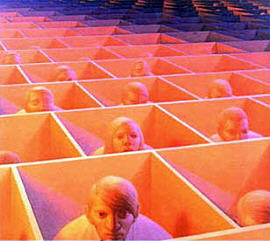

Why do we kill each other? Human psychology seems as if it depends upon the existence, whether real or fabrication, of an evil enemy to reaffirm its own goodness and sanity. It is as if we are resigned to the perceived reality that separate entities must have conflicting ideals and motives, thrusting each side into competition. The ultimate goal in competition is elimination of the opposition. Since recognizance of humanity evokes human compassion, elimination is facilitated by regarding the opposing entity as an abstraction. In our attempts to create this disjointed feeling of distant hatred, we demonize and dehumanize our enemies, using the media to perpetuate these perceptions. Such dehumanization is aided by the simple fact that people from different parts of the world look and act differen t from one another. It’s absolutely shocking to me that many political cartoonists oftentimes depict people of different races stripped to their most stereotypical characteristics and later rationalize that stereotyping is necessary for mass recognition. We latch on to a pronoun mentality of “they want to kill us,” appealing to our most primal instincts, and compelling “us” to believe that “we” fight for “our” very survival. As a result, entire societies come together as one to fight the perceived enemy. There are no ambiguities in war – it is simple. We unite in a single cause and work to achieve our goals. We benefit socially from newfound camaraderie. Health increases and suicide rates decrease. New technologies emerge from rapid industrial development. Privateering provides employment and boosts the economy.

t from one another. It’s absolutely shocking to me that many political cartoonists oftentimes depict people of different races stripped to their most stereotypical characteristics and later rationalize that stereotyping is necessary for mass recognition. We latch on to a pronoun mentality of “they want to kill us,” appealing to our most primal instincts, and compelling “us” to believe that “we” fight for “our” very survival. As a result, entire societies come together as one to fight the perceived enemy. There are no ambiguities in war – it is simple. We unite in a single cause and work to achieve our goals. We benefit socially from newfound camaraderie. Health increases and suicide rates decrease. New technologies emerge from rapid industrial development. Privateering provides employment and boosts the economy.

Does human progress depend largely on human suffering? One of the principle debates concerning civilization’s origins asks if humans were first driven together by war. Recent archaeological finds in Peru have uncovered relics of a 3,000 year old military civilization composed of several nomadic tribes forced to unite in order to survive then overcome neighboring competition. Such logical reasoning still appeals to our sensitivities today. Alliances are made, broken, re-formed, and revised in accordance with a society’s priorities. What is the true nature of human evil? The human faculty for the rationalization of the irrational is an integral component of humanity. Perhaps then, the true nature of human evil is being human. Thomas Hobbes stated in Leviathan that “the life of man [is] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Sometimes it can be difficult to disagree with him.